Allegedly—I don’t have an inside line here, but what we can all read in the papers sounds pretty bad—allegedly, it went down like this1:

A dealer in Florida told an investment-minded collector that he had a sweet deal with the Warhol Foundation for fresh material from the Foundation at around 10% of market price; if the collector would come in on these works for a half-share, the dealer could flip the works at market price and split the 900% profit.

Some of this is true: the Warhol Foundation is a separate legal entity from the Warhol Museum, and, unlike a museum, it is not deaccessioning artworks from a sacrosanct collection, but performing a part of its chartered mission to distribute its rich holdings by the prolific artist to support the Foundation’s goals. (Those goals include giving away hundreds of major works to major museums, giving away huge cash grants, and doing a lot of expensive outreach and research)2. That is: the Foundation is allowed to sell stuff; indeed, they are tasked to do so.

It’s also the case that there is a ton of “gray area” in the world of Warhol. There are test prints, unsigned this-and-thats, signed things that may or may not be artworks. The man blurred the line between art and commerce, life and and art, documentation and imagination—so there really are things that you’d have to hold up to the light and ask, “Is this art? And even if it isn’t, is it valuable?”—and not know the answer right away.

And, Warhol really is a liquid asset: they go for a lot, and they go readily. That’s not to say you can ask anything, but the material is so regular3 and there’s so much of it going through public sale all the time that it’s easier to say what the market price for a particular Warhol work is.

That much of the story is based in reality.

The rest of it, allegedly, is based in fantasy. Allegedly, the Warhols in question were fake, not test prints or authorized ephemera, and had no resale value whatsoever. Allegedly, the dealer found or created these fake works and then created fake email addresses from a fake Warhol Foundation employee and offered these fake documents to the collector to demonstrate that the works were real and had the blessing of the Warhol Foundation.

And more to the point, the Warhol Foundation does not reach out to dealers just out of prison for selling fakes4 and offer them 90% knockdowns on legitimate artworks—why in god’s green acre would they?

II. The Worst Way to Fake Art.

Whether the allegations are true or not, they are a case study in the worst possible way to sell fake art. We’ve written before on good ways—like Ken Perenyi’s Martin Johnson Heade forgeries5—and bad ways, like Knoedler’s sale of fake Pollocks. But this is the worst. I’m not talking morally—all forgery is bad, stealing is wrong, and crime doesn’t pay, etc.—but just logistically, how could this possibly succeed?

The whole value of an artwork is its durability as a record of intentions. If it’s real, it records the intentions of the artist; if it’s fake, it documents a crime. A fake artwork can slip into the market from time to time—it’s bad if you sell one, but honest dealers can make mistakes without committing fraud. But when you go through the additional step of making fake email addresses, you document an intention to deceive—so you’ve committed fraud by faking the documents. And since it’s email, it’s also wire fraud, so you’ve got the Feds on your ass if you didn’t already. With a profile as high as Warhol’s, with an institution as visible and transparent as the Warhol Foundation, the artworks, the provenance, the transactions, the emails—they’re going to get scrutiny, and not in a hundred years’ time but in months. And the evidence is going to point directly at the fraudster when it does.

III. Who has the time?!

As an honest dealer, of course I recoil at the thought of faking artwork, emails, and receipts, but you have to also goggle at the effort. All the running around they did, making weird aliases for gmail accounts, doctoring PDFs—presumably making the damn artworks as well. Lordy, who has the time?! Do you know the amount of work it is offering legitimate artworks to legitimate collectors? These weekly e-blasts are an absolute joy to bang out every Tuesday compared to the inane clickety-clackety of offerings and accounting I do the other six days a week. Criminal conspiracies to defraud that you know are almost certainly going to be uncovered within five years? There’s got to be a better way!

Which leads to a question I never get asked but secretly hope all my readers one day will:

As a dealer, isn’t it easier to sell a legitimate painting for $100,000 than to sell a fake Warhol for the same price? Isn’t being an honest art dealer enough?

And this is why this bafflingly stupid crime matters: the answer is no, and that is the single most worrying datapoint I can give you about the economy of the artworld today. In spite of a lot of handwringing about inclusivity and expanding the canon and looking high and low for overlooked gems, the golden circle of reliably liquid high-value artists is shrinking. Twenty-five years into the new century, there is more money in the artworld than ever before, and fewer artists represented in that asymptotic spike of value. You can buy some of the greatest paintings ever painted for $150,000, but it’s much, much easier to sell a sketchy-as-hell Warhol that just fell off the back of a truck for the same price, and even if you personally weren’t about to buy either, the observation should be a sobering one. How on earth did a raft of fake Basquiats get into a major museum show?6 How did a much-restored da Vinci make half a billion dollars at auction? How can Warhol after Warhol bring a million dollars? The answer is all basically the same, and it isn’t “Florida Man,” though that’s tempting, but with apologies to William Butler Yeats for the inversion: the falconer cannot hear the falcon; the gyre shrinks; things fall apart.

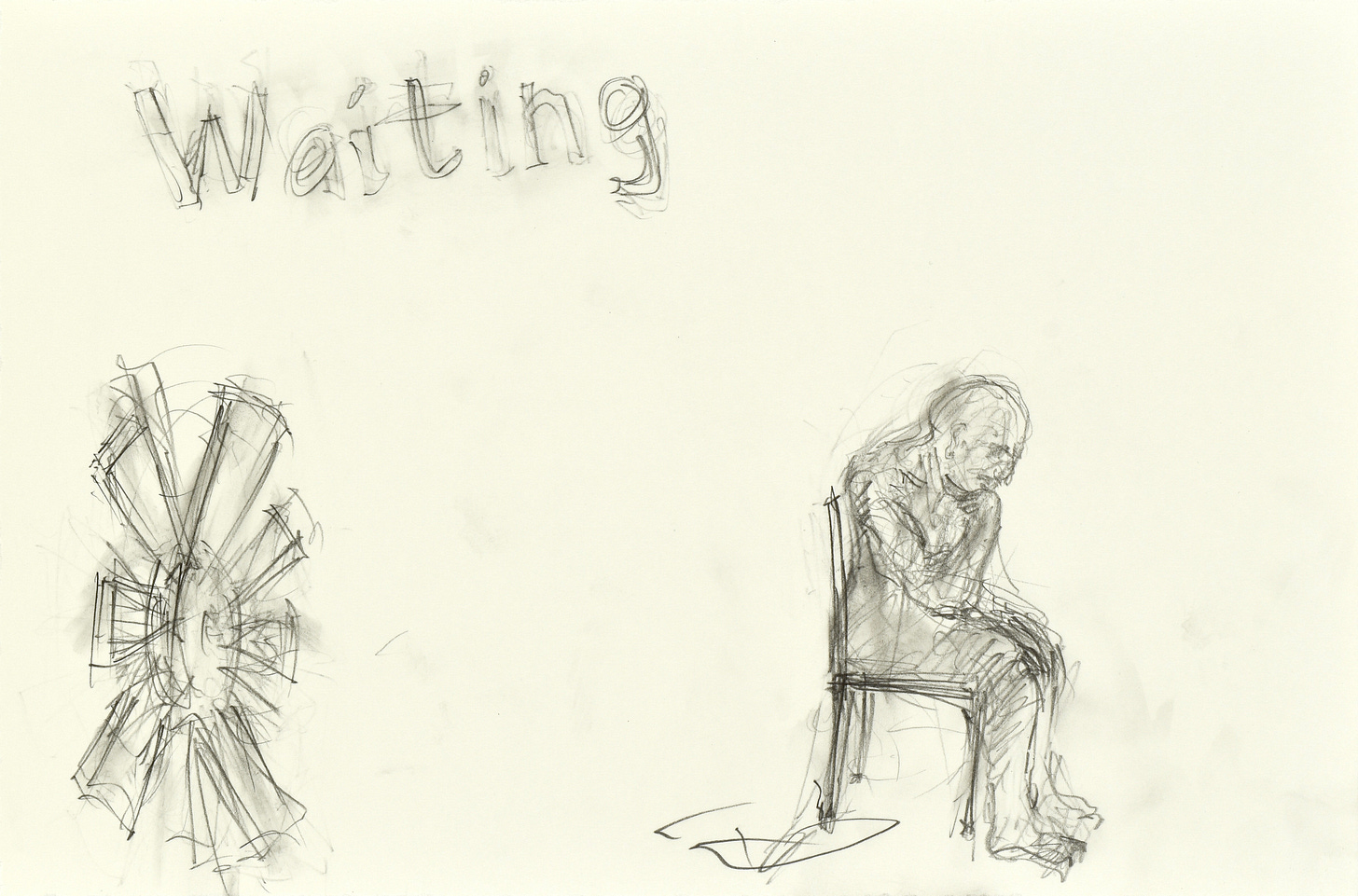

Opening Thursday: Paul Shore | Whirligig.

The waiting is over! Join us THIS Thursday night, September 12, as Jonathan Miller Spies Fine Art presents Paul Shore: Whirligig, at CG Boerner. Join us for a reception with the artist on September 12, from 5-8 PM at 526 West 26th Street, 419. On view through October 5, 2024. Thanks for reading, and we hope to see you at the show!

Jonathan

jonathan@jonathanmillerspies.com

Julia Jacobs, “Family Says It Spent $6 Million on Fake Warhol Artworks,” The New York Times, Sept. 2, 2024, section C, p. 4.

Its mission statements and policies are public-facing and pretty legible for the layperson.

That is, there are well-documented multiples and variants. Soup cans, Brillo boxes, Marilyns: all made on an industrial scale with industrial processes: this is the closest thing in the artworld to buying or selling a stock.

Read our story on the Perenyi Heade forgeries here.

Here’s a nice gloss on the fake Basquiats in Orlando by the inimitable Bianca Bosker.