Federico Castellón is Dark, but was he a Surrealist?

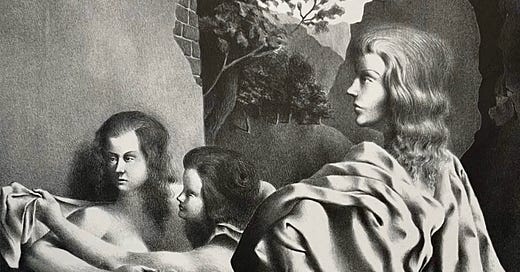

Federico Castellón (1914–1971), The New Robe No. 2 (Vestido de Gala), detail, c. 1939.

“I knew that there was something extremely disquieting about my work,” Federico Castellón summarized, without regret, at the end of his life. “And I knew it’s not pleasant, sometimes inclined to be a little morbid.”

Death, war, and the duskier themes of the Brothers Grimm: these are the subject matter of the painter and printmaker, Federico Castellón. He resisted the appellation of Surrealist, but critics and historians have puzzled over a better term. He proposed “Romantic,” and tried to position his imagery outside of history, but the time period—with mature work beginning in the 1930s—and the eerie subject settles the matter.

That subject matter was suffused with the violence of his early childhood in Spain in the early 1920s—violence distorted into fairy-tale proportions by his young mind:

“At one time, two of my brothers and I were . . . supposed to have been at the movies . . . but we didn't go to the movies, I guess we used the money for buying something . . . It turned out the movie we were supposed to be at was bombed and a lot of people were killed and hurt . . . My mother was tearing her hair out and crying, yelling and what not . . . She thought we were dead and here we were alive and we got beaten up for it.”

Castellón’s recollections of his childhood in Spain is not always entirely reliable, but what is clear is that his father decided, “‘The hell with this, we're going to lose the family piecemeal. Let’s all go.’ So we all came over.”

His parents sold the family leather business and sought similar topography to their native Almería, and came up with Flatbush, Brooklyn. The timelessness, the uncanniness of the Old World stayed with Castellón, haunting his art as de Chirico-esque ruins. Much like George Ault’s1 and Lyonel Feininger’s2 encounters with Europe, Castellón’s remembered Spanish towers stretch into lumbering hulks—distortions that withstood revisiting them decades later:

“When I went back to Spain to see the great plaza where the enormous cathedral was at one end of it, I discovered the plaza was only about one hundred feet in diameter and the cathedral was a local village church, that’s all.”

Those distortions were nonetheless Castellón’s foremost concern. His life in Brooklyn was deeply inward; drawing offered an outlet:

“I very often attribute my becoming an artist to being a very fine kid and that children are sensitive as hell. Also, they’re the worst little bastards in the world and my life was miserable as I remember it as a child here in this country, because I was always known as the little Spanish kid . . . the implication wasn’t pleasant. I was always told that in a manner of rejection and I remember being in the house, oh, for days on end without daring to move out of it, you know, without even going to school, and limiting myself to drawing because I couldn’t write. I had no other activities and my mother yelling at me, get out, get some air, play, do something! So I'd go out in the street and just hang around and watch the other kids play for ten minutes and back in the house and drawing again. It seemed the only activity that I could pursue and save my sanity, somehow.”

He was profoundly gifted as a draftsman and had a relentless urge to render, in black-and-white (he lusted after a box of pastels, but could never afford his own), the strangeness of life within his own skull.

I don’t usually dwell on the biographical details of an artist’s early life—nearly everyone who makes a career in the arts has a story about an alienating encounter on the playground and an art supply fetish. But I linger here because Erasmus Hall High School in Flatbush was the end of Castellón’s formal education, and before graduating from that stony edifice, he had a sell-out show3 at a highly-esteemed Manhattan gallery. And the same thing that got him that show was the reason Castellón isn’t already on your radar—and that thing is Diego Rivera.

II. Printmaker.

It’s hard to overstate the significance of Diego Rivera in New York in 1931. He came to the US for a series of mural commissions and museum shows, each adding further to his rockstar status,4 and Castellón was at the right place at the right time:

“He had come to New York to do the murals at Radio City and there was a friend of my family who had another friend in a Mexican organization . . . Rivera was very kind, extremely kind, and asked to see my work. Ordinarily, you know a little snot nose comes up to him, loss of reputation, you know, ‘Oh God, am I involved in this?’ But he was very kind, he was very anxious to see my work and asked me to bring it around, which I did. And he said, ‘Leave it here for a few days, I really want to study it.’ Which I did. And several days later I went back to pick it up and Rivera said, ‘Well, I’m keeping these six.’

It’s not a small thing for a high school kid to sell a half-dozen drawings to the world’s most famous muralist, and Castellón appreciated the immensity of the honor:

“Once I walked—he was staying over at the Hotel Brevoort on Fifth Avenue, lower Fifth Avenue, and we walked all the way up to Radio City on Fifth Avenue. So it’s a long walk, you know, and Rivera at that time had had his pictures in the paper and everything and I thought, gee, I’m walking along next to this great artist and I’m sure that everybody’s so jealous of me. Nobody looked at me. Here’s Miss America I’m walking with; nobody cares. So I began waking up, you know.”

And this disillusionment turned Castellón towards something more intimate: smaller subjects, smaller works—for a smaller sort of success. An exhibition of Castellón’s oils at Sotheby’s this month showcased just how small we’re talking—intimate, and exquisitely crafted.

Rivera did more than just buy a few drawings; he put Castellón directly in touch with Rivera’s dealer of prints: Carl Zigrosser.

At that time I was very happy. ‘He loves it enough to keep six; isn’t that wonderful!’ He said, ‘I want you to bring the rest up to the Weyhe Gallery. I've spoken to Carl Zigrosser about you and he's expecting to see you.’ So I brought them up and Carl Zigrosser liked them and he kept them there and that became my gallery.”5

Castellón called Zigrosser “my guardian angel” but Zigrosser was an important figure far beyond watching over Castellón. When the print and book dealer Erhard Weyhe opened his American gallery in 1919, he hired Zigrosser was hired to direct it. Weyhe specialized in prints by the best artists in the world—from painters who made prints like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso to committed printmakers like Rockwell Kent and Louis Lozowick. Zigrosser had worked for another major print dealer—Frederick Keppel & Company—and at Weyhe, he became a print specialist for his entire career. He’d later author the definitive texts on several printmakers as well as major surveys of printmaking as an art form—and he had a knack for getting painters to make prints.

Among these was Diego Rivera, whom Zigrosser met in 1931. Rivera was sympathetic to prints as a revolutionary medium—there’s a great survey of the Mexican printmaking tradition at the Met right now—but Rivera already had a successful public artform at his disposal—and like Castellón said, he was “Miss America” in that department. Zigrosser convinced Rivera to make some prints—and the dozen that Rivera did for Zigrosser at Weyhe are among the only prints he ever made.

And this was the moment that Castellón walked into Rivera’s life: a promising Spanish kid looking for a gallery, escorting an international superstar muralist who just happened to be excited then and only then, about making prints. Zigrosser showed and sold Castellón’s drawings immediately, and within a few years, he’d convinced the artist to make prints. It became the focus of his career.

And the success of those prints earned Castellón several travel grants to Europe, putting an expert shine on the extraordinary natural gifts that he had honed as a lonely introverted immigrant in Flatbush.

Zigrosser left Weyhe in 1940 for a curator position at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where he stayed the rest of his life. In 1970, Castellón made plans to move permanently to Europe; when Zigrosser learned this, he wrote his old friend to lament that they’d seen so little of one another in recent years. The week of April 7, 1971, Castellón paused in his packing to give an interview with Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art—an interview from which most of the remarks above are culled. Before Castellón boarded a plane, he died of a sudden and unnamed ailment on July 29, at the age of 56.

Read our article on Ault’s Memories of the Coats of France here.

Read our article on Lyonel Feininger’s Ruin by the Sea here.

The show was recollected by the artist to have netted him $130—a princely sum for a kid working in an industrial bakery, but I can’t confirm that it actually sold out.

And when Nelson Rockefeller put his foot down on the depictions of Lenin in Rivera’s mural at Rockefeller Center, Rivera’s legend was elevated further, even as his career took a hit.

Oral history interview with Federico Castellón, 1971 April 7-14, full transcript available here.